|

Several

weeks ago I needed to move Otter off a 48-hour mooring, to another safe

location where I could leave her ready for taking her home to Maestermyn

marina. Throughout the first few months of the year, stoppages had

resulted in the canal being blocked immediately east and just a mile or

so west of my normal mooring, so Otter was moved to the upper end of the

Llangollen Canal for a few months so that we could still enjoy

occasional weekends away, and take the school kids for evening trips.

However, by mid March the stoppages had cleared and it was time to take

her home. My first problem was that she was facing the wrong way. Moored

outside the Sun Inn, at Trevor, taking her to Llangollen to wind her

would have involved cruising the 300metre narrows, a lift bridge, the

500metre narrows, through the online town moorings, the short narrows in

the town, then down past the horse-drawn-boat centre to wind at the

marina. Then, of course, back through it all in the other direction. Several

weeks ago I needed to move Otter off a 48-hour mooring, to another safe

location where I could leave her ready for taking her home to Maestermyn

marina. Throughout the first few months of the year, stoppages had

resulted in the canal being blocked immediately east and just a mile or

so west of my normal mooring, so Otter was moved to the upper end of the

Llangollen Canal for a few months so that we could still enjoy

occasional weekends away, and take the school kids for evening trips.

However, by mid March the stoppages had cleared and it was time to take

her home. My first problem was that she was facing the wrong way. Moored

outside the Sun Inn, at Trevor, taking her to Llangollen to wind her

would have involved cruising the 300metre narrows, a lift bridge, the

500metre narrows, through the online town moorings, the short narrows in

the town, then down past the horse-drawn-boat centre to wind at the

marina. Then, of course, back through it all in the other direction.

Given

that it was the first Saturday morning since the stoppages, and that I

was single handed, I didnít relish the idea, so the possibility of

reversing her to the Bryn Howel winding hole, about a mile back down the

canal, felt like an attractive prospect.. Given

that it was the first Saturday morning since the stoppages, and that I

was single handed, I didnít relish the idea, so the possibility of

reversing her to the Bryn Howel winding hole, about a mile back down the

canal, felt like an attractive prospect..

About a year ago I had read an article in Waterways World, by Chris

Deuchar, in which he discussed a method of single-handed reversing. The

method intrigued me and Iíd been itching for a set of circumstances to

arise where I could try it out. So, no praise to me for this idea; itís

not mine!

The other thing that I should mention, of course, is that taking photos

of yourself on a single handed reverse is a bit tricky, so the photos below were

taken at a later date on the Montgomery Canal, when I had a friend stand on a

bridge and witness a contrived set of circumstances, set up for the purpose of

this article.

So,

hereís how itís done. First, prepare the boat by ensuring a clear-passage

through the cabin, removing any obstacles from the aisle through the boat. Next,

put the pole in a handy position on the roof, at the bow, then return to the

stern, set the boat mid-channel and tie the tiller either dead-centre, or, if

your prop has a tendency to cause your boat to pull to one side, tie the tiller

just off-centre to compensate for itóuse an easily released slip-knot!. So,

hereís how itís done. First, prepare the boat by ensuring a clear-passage

through the cabin, removing any obstacles from the aisle through the boat. Next,

put the pole in a handy position on the roof, at the bow, then return to the

stern, set the boat mid-channel and tie the tiller either dead-centre, or, if

your prop has a tendency to cause your boat to pull to one side, tie the tiller

just off-centre to compensate for itóuse an easily released slip-knot!.

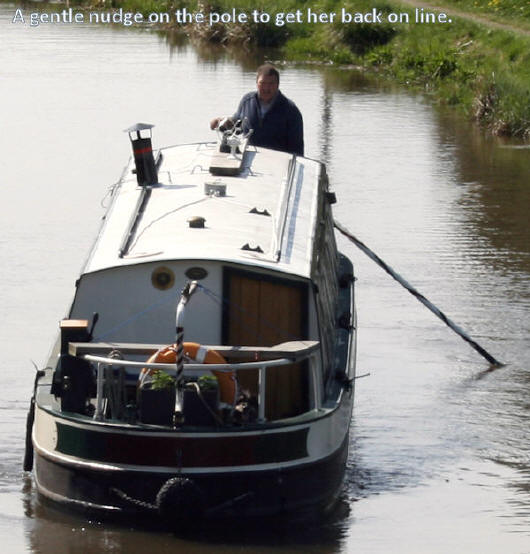

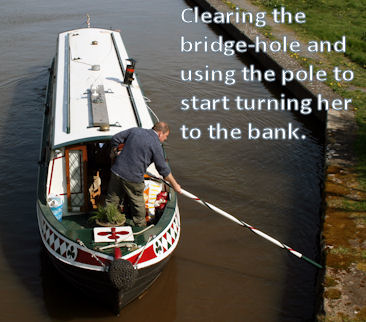

Next, engage reverse at a slow-running pace and go quickly to the bow,

take hold of the pole and look along the roof to the stern, observing your

course. Youíll need to keep the boat running approximately central to the

channel and, at the slightest deviation from this course, use the pole to give a

gentle nudge to swing the bow slightly to one side or the other, so as to

correct it. The trick is to respond quickly, with slight movements of the

poleóthis, of course, is very much the same as the method we use for steering

forwards, but we tend to do that instinctively, rather than analytically.

When I tried this, my first hundred yards or so saw me pointing from bank to

bank, struggling to keep a good course; I was over steering, which is what most

novice steerers tend to do. Gradually, though, I got the feel for it and soon

realised just how true a course itís possible to hold.

I found that bridge-holes didnít pose the problem that I expected them to, even

when they coincided with a bend. With both slow speed and early adjustment of

the steering, I comfortably slipped under the bridges and then corrected my

course as I emerged the other side. The biggest problem that I encountered when

I did this Ďfor realí, was the reaction of other boaters.

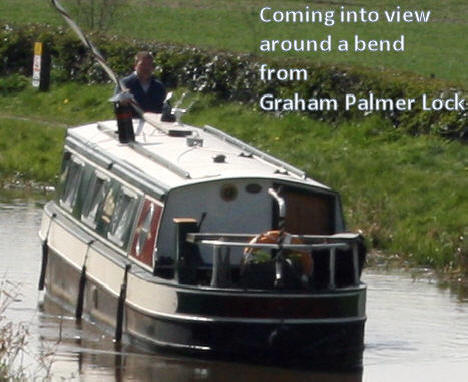

Anyone

familiar with the Trevor to Bryn Howel length will recall the railway bridge

which, whilst being fairly wide, has a sharp, 90o bend immediately preceding it.

Imagine the reaction I got when an approaching hire boat spotted my stern coming

around the bend, apparently driverless! To the sound of their expletives, I put

the pole on the roof and ran through the cabin (which is why you need to keep a

clear passage through the boat), then slipped the knot on the tiller and engaged

forward to regain normal control of the boat. Anyone

familiar with the Trevor to Bryn Howel length will recall the railway bridge

which, whilst being fairly wide, has a sharp, 90o bend immediately preceding it.

Imagine the reaction I got when an approaching hire boat spotted my stern coming

around the bend, apparently driverless! To the sound of their expletives, I put

the pole on the roof and ran through the cabin (which is why you need to keep a

clear passage through the boat), then slipped the knot on the tiller and engaged

forward to regain normal control of the boat.

Otter is only 40ft long, so she responds quickly to the tiller and can turn on a

sixpence. Sceptics tell me that this method of reversing is of little or no use

to anything much longer than thisóbut the sceptics that I spoke to donít drive

Pipers! It will be interesting to hear from other members whoíve tried this in

the larger boats.

Return

to Pipeline Index Home Page

|